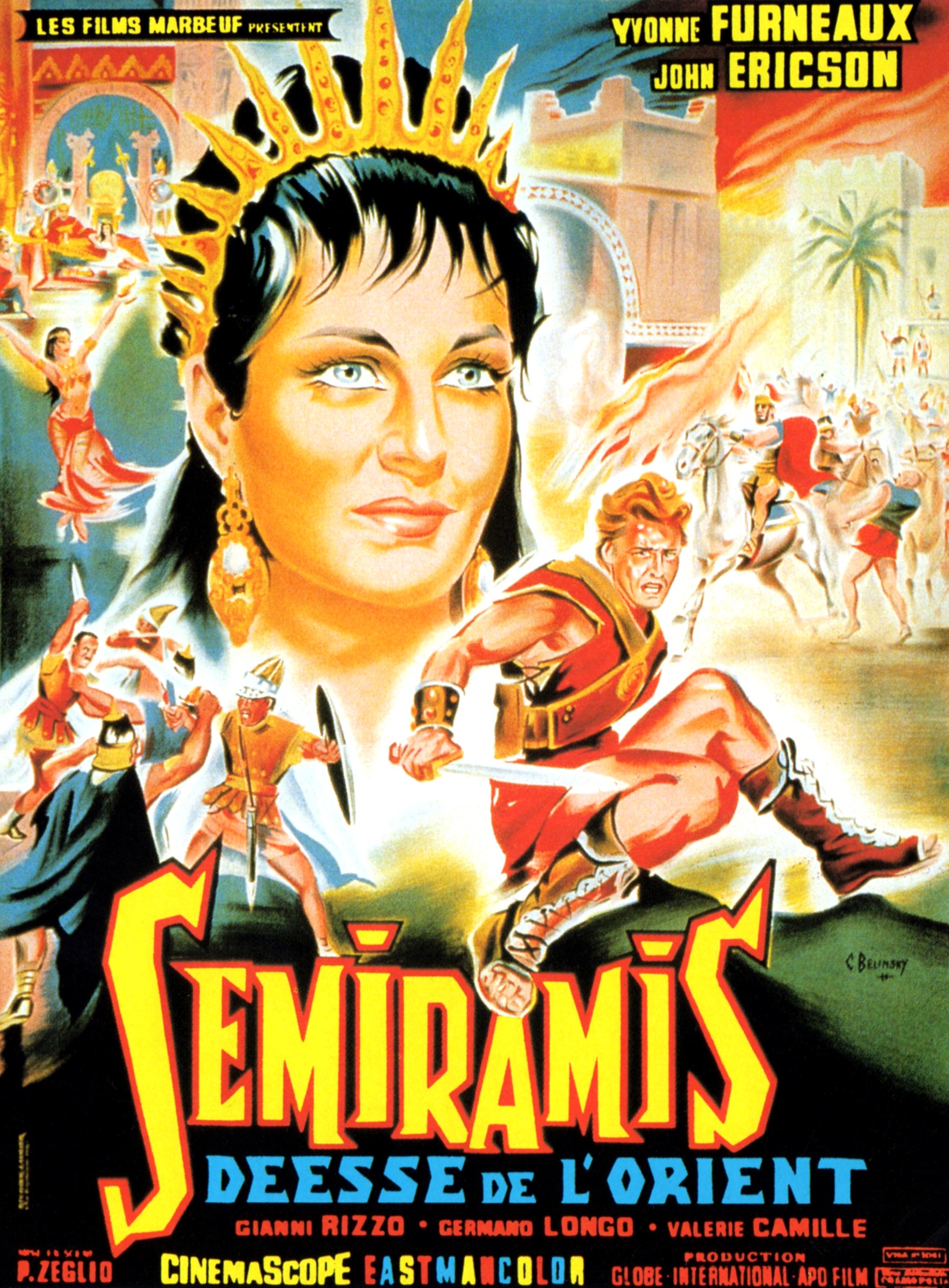

Each culture told her story a bit differently, but she was always a beautiful, strong, riveting character who inspired works of art. The Greeks then changed her name to Semiramis, said that she took a handsome soldier into her bed every night and then had him killed in the morning, and claimed that her son eventually had her murdered because of the shame that her rampant immorality brought to the country. On the negative side, she was said to have killed her husband to seize the throne and to have committed incest with her son. She acquired a divine connection to the goddess Ishtar and became both the founder of the city of Babylon and a great military leader. Naturally, as her story was recounted through oral tradition over generations, it became embellished, sometimes outrageously. It was unheard of at the time for a woman to rule Assyria, and the fact that she preserved the kingdom so that her son could begin his reign over a strong, peaceful country assured her a place in history. When he died, their son, Adad-nirari III, was still a minor, so his mother held the throne for five years until he came of age. Sammuramat was the wife of Assyrian king Shamshi-Adad V, who reigned from 824–810 BCE. Like many semi-historical, semi-mythical figures, she really existed, but over the centuries, the very few verifiable facts about her have become encrusted with a variety of legends. His 1748 tragedy Sémiramis had everything: regicide, matricide, repeated supernatural intervention, a brush with incest, abundant political intrigue and conniving, and even a mad scene (which Rossini wrote, most unusually, for the bass)-all set against the exotic backdrop of Babylon and its Hanging Gardens.Īt the heart of the story is one of the legendary figures of the ancient world, the Babylonian queen Semiramis.

Voltaire’s dramas often put people into extraordinary situations that force them to make gut-wrenching decisions, and they inspired composers from his contemporary Rameau to Bernstein.

Like Tancredi, Semiramide has a libretto by Gaetano Rossi based on a play by Voltaire. His final five operas premiered in the French capital. But in 1824, Rossini was lured to Paris by the musical directorship of the Théâtre des Italiens and encouraged to remain there by a contract and pension from Charles X. After all, since the premiere of his opera Tancredi in the same theater ten years before, he had been on a long, glorious run, one that had solidified his position as the finest composer of his generation in Italy and one of the most famous men in the world. No one at the 1823 premiere of Gioachino Rossini’s Semiramide-at Venice’s Teatro La Fenice-had any idea it would be the composer’s last opera for the Italian stage.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)